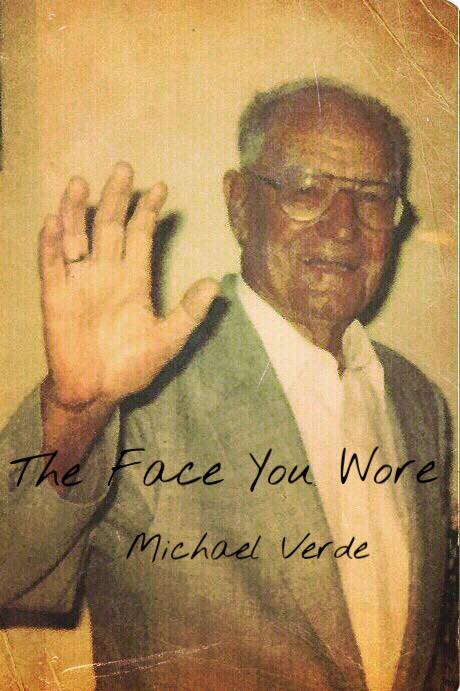

For this blog post I would like to share a story that changed my way of understanding the source of the suffering that we habitually associate with people with Alzheimer’s disease. It changed too my understanding of what people with dementia, in any of its myriad irreversible forms, most need from us. And, finally, it changed my understanding of what it means to be a person, no matter what that person’s signature “with” is, whether it is a person with dementia, or with depression, with a disability, with a stigmatized sexual orientation, with a criminal record, or with … or with … or with…

*

The chattering voices of family filled my grandparent’s house. We had returned here to Barber’s Hill, Texas from our various homes across the state for my grandfather’s funeral. Only during our annual Christmas reunions were this many of us together at one time.

My mother found me visiting with my uncle on the couch and suggested that I get one of the cassettes of my grandfather telling stories and play it. I thought it was a great idea, and asked my grandmother where she kept the tapes. I had made the recordings years ago, the very week after I returned to Texas from Paris, where I had gone to—as I put it then—“find myself.” In fact, I had quit school at the University of Texas to do so. Growing up in a small, country town, I had always fantasized that when a person graduated from university he was a new kind of person, transformed—sort of like Pinocchio the toy becoming Pinocchio a real boy, or Gandalf the Grey becoming Gandalf the White. So a year before I graduated, I dropped out of school and moved to Paris and commenced my search for my self. What made me think that the transformed me would be in Paris is one of those things I chuckle about now. My best guess is that I wanted to be a writer back then and Paris meant Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Joyce, and the mecca of ex-pat American writers.

“Grandma,” I asked, “can you tell me where you keep those recordings I made of grandpa years ago?” She knew exactly where they were, of course. My grandmother had not been the secretary of the First Baptist Church for thirty-plus years because she misplaced things.

In Paris, with neither job nor homework (or much money), I brooded over coffee, trying to work myself into a deep existential angst that would culminate, ideally, in a life-changing insight into myself. And to accomplish as much I went to fairly absurd lengths. For instance, among other makeshift exercises concocted to effect enlightenment, I assigned myself a koan. A koan is a seemingly nonsensical saying that a Buddha master will give to a disciple who comes to him seeking enlightenment. “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” for example. Or, “how many lions are there in a single hair?” The idea is that wisdom runs deeper than logic and that by confounding all rational explanation a koan provokes one’s monkey mind to hush so that one’s deeper, wiser, original mind can get a word in edgewise. Paris, I suppose, wasn’t foreign enough for me to find myself. I would have to make it all the way to the East, if only in the confines of my little studio near the La Motte Picquet metro stop, where I sat once a day on the thin carpet with the lights out, meditating on my koan, which went as follows:

Show me the face you wore before your mother and father were born.

Six months of sitting quietly in a candle-lit studio for forty-five minutes a day trying to get my mind around how a person can even have a face before his mother or father are born yielded no epiphanies. For a while I reasoned that the answer to my koan hinged on reincarnation, an idea which my Southern Baptist upbringing strongly suggested was sinfully superstitious. I spent many meditative hours trying to get over my reflexive resistance to the idea that after you died you quite possibly came back here for a second round, or a third, fourth, or ten thousandth.

After eleven months of this fruitless ritual, the answer finally surfaced: my grandparents. If my intent was to find myself I had come a long way in the wrong direction. I wasn’t in Paris. I was in east Texas, in the memories of the people in whose past my present was forged. My grandparents wore the face I wore before my mother and father were born. Ten days later I returned to Houston. On the way to my parents’ house from the airport, I asked to stop at Wal-Mart, where I purchased a tape recorder and three packs of six, 90-minute cassettes. The next morning I called my Grandpa Leonard in Barber’s Hill, Texas and told him that I was coming to stay with him for a while.

Over the next two weeks my grandfather and I drank a lot of coffee, I on the couch and he in his orange recliner. Between us, next to a paper towel-stuffed Folgers coffee can (his spittoon), a tape recorder whirred…

… Story after story, tape after tape. I listened, and when I thought I heard a thread that might lead my grandfather to a new set of memories, a new trail of tales, I asked a question. I kept them simple, and for the most part open-ended: “How did you meet grandma?” “What was my mama like when she was little?” “What was your first job?” When I began the project I feared the tape recorder might distract him, freeze his tongue by putting him on the spot. It didn’t. If he was saying something like, “We came up to the bridge” and the tape ran out, he would halt his story and while I flipped the tape he’d contribute to the spittoon. When I was ready, I would hit play, nod, and he would pick up right where he left off: “…and we crossed it.” I recorded close to twenty hours of my grandpa telling stories. I took my grandfather’s stories and wove them together into a novella that I entitled Over and Under and Back from Whence You Came. That was the ditty my grandfather’s father employed to teach him how to tie a tie: “You take one end of the tie and go over and under then back from whence you came. You do that twice and knot it.”

No one knew at the time that my grandfather had Alzheimer’s. It is not a disease that strikes you like a stroke or a heart attack. It happens to you after it has already happened to you—

like growing up, but in the wrong direction. It started with names; it ended with faces. The last face to go was his own. It is a fact about Alzheimer’s disease that seldom gets mentioned, maybe because when it happens so many other, more functionally relevant debilities have assumed center stage, but one of the signature symptoms of having advanced to what is called the final stages is that one’s face assumes a conspicuous absence. The term “plasticity” is often used to describe the change—or the “lion’s face.” The latter description is an exquisite example of the tenacity of myth, of why science, particularly medical science, is as informed as much or more by story as by number. The lion-bodied sphinx offers the pilgrim an inscrutable face, the riddle of an echoless gaze. The demented disturb us because the answer to the “disease” is as simple as it is impermissible to say: Over and under and back from whence you came.

My family’s response to the sound of my grandfather’s voice emanating from the speakers of my little brother’s portable stereo—a jam-box they called it then—surprised me. Instantly, and as if by some ancient instinct, my grandparent’s children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren began moving to the living room, some in pairs, some in larger groups, some singly. I watched as we formed a large circle around that stereo. We could have just as well been gathering around a tribal fire in a cave in which human history began with the first story ever told.

“I never shall forget…” proclaimed my grandfather’s voice into the silent room.

When I looked around the circle of us standing in rapt attention listening to my grandfather’s story, it dawned on me that my grandfather had pulled a trick on Alzheimer’s disease, because when Alzheimer’s disease came to take his self, his self was gone. He had already given it away. He had taken his time, his attention, his love and he had communicated his self into ourselves, into our bodies—better, into our body: the body we shared as a family. No disease could ever touch, much less disintegrate, a self thusly composed.

Here is the story that I played for my family that night, the evening before my grandfather’s funeral. Of the scores of stories that he shared with me, this was his favorite—the only story that he told that brought a tear to his eye. He was not a crier.

My grandfather was demonstrating to his sister Bennie how he could strike a match with one finger, just like his father. He was ten years old, she was fourteen. They were sitting on a bale of hay. The bale was on the side of his granddaddy’s barn. After numerous failed attempts, my grandfather told his sister he would show her how it worked tomorrow, and they went into the house.

It turned out that he was a little better at the trick than he thought. One of those match-heads had actually lit on the tip of his fingernail and fallen into the hay bale. But he and his sister were already in his grandparent’s house before the bale went up in flames. The hay served as kindling to the barn. It burned to the ground. And everything in it did too. What was in it was his grandfather’s crop of cotton for the year. He was a cotton farmer. And not only that year’s crop but the seed crop that had been put aside for next year too. It was his grandparent’s entire source of income.

At this point in the story my grandfather said to me, “That was the worst day in my life, boy. I had wiped my old granddaddy out. Everything he owned. With one careless act I had ruined the livelihood of the man who took me in and raised me like his own child.”

My grandfather was adopted by his grandparents when he was six. His parents divorced, and on the day that they broke the news to him—they happened to be at his grandparent’s house visiting—they gave him the choice of choosing which parent he wanted to live with. He told his parents that if he could not have his first choice, which was to live with them both, then he would rather live with his grandparents. His grandparents loved the idea.

“I was wiped out, boy. Don’t you know it?” That was the phrase my grandfather used again and again to describe how he felt when he burned down his grandfather’s barn.

He was sitting on a stump sobbing when his grandfather arrived home that day. His grandfather was the judge of that area of Oklahoma. The people who lived there chose him to serve in that capacity unofficially. The county had an official judge, but the county seat was miles away, and in those days people in rural areas often selected a person in their community whose judgment they all trusted to settle local disputes without involving any official governing bodies. His grandfather’s name was T.E. Roe—the “T” for “Thomas” and the “E” for “Edison.” When his granddaddy disembarked from his buggy and made his way across the dirt yard to my grandfather, I’m guessing it was judgment day, indeed, for that ten-year-old boy.

Three times, my grandfather told me, he tried to tell his grandfather what he had done. But each time he broke down and couldn’t get the story out. There wasn’t much to explain, really. The story could be read easily enough in the cracking embers and smoldering ashes of what was left of the barn.

After his third failed effort at getting the story out, my grandfather’s grandfather sat down beside him on the stump. He put his arm around my grandfather’s shoulder and pulled him gently to his side.

“Your old granddaddy has made a mistake or two in his life,” he said. “The sun will come up tomorrow.”

When my grandfather told me that story with the cassette recorder whirring between us, he looked deep into my eyes and said, “Now, boy, that’s love.” I could barely feel my body in that moment, which felt to me then, and still does, as the holiest of my life. “I’m seventy-seven years old,” he added, “and I pray that before I die I learn to love like my old granddaddy loved me.”

When he said that to me, I saw it: the face I wore before my mother and father were born.

And I’m confident that that was the face that my grandfather’s granddaddy wore when he said, in the moment of truth on what had been up until then the worst day of my grandfather’s life: “Your old granddaddy has made a mistake or two in his life. The sun will come up tomorrow.”

I have often wondered where that old man—and by “old man” I mean my grandfather’s grandfather—came by the wisdom and the compassion in that instant to understand that in addition to raising cotton, he was raising a child. And between the two, there was no comparison of worth. Where there had been a barn, that old man built a bridge. Between his heart and my grandfather’s heart, a bridge appeared out of nowhere and invited that little boy to come home, to return to the family from whose membership he thought he had disqualified himself. The boy who was “wiped out” was brought back to a life that he thought was over, to a life of belonging and mattering. His grandfather’s offer of love instead of judgment healed that little boy right there and then.

I often think about that moment because in it, my life too was changed. I say that because if my grandfather’s grandfather had not forgiven him in that way, my grandfather’s ability to love my mother in the way that he did would have been, I’m sure, profoundly impaired. I believe that because I really do believe that my grandfather was, as he said he was, “wiped out.” I take metaphors very seriously—years of loving literature and teaching it will do that to one’s imagination. Emotionally, spiritually, imaginatively—however you want to put it—I believe that when my grandfather thought he had ruined his grandfather financially that he experienced himself as wiped out. In as real of a sense as sense can sense, he felt himself as no longer alive in the way that he had been alive before. Though he had not died, his life was over. He sat on that stump, gone.

If my grandfather’s grandfather had not brought my grandfather back into his body of belonging in that moment, if he had not assured my grandfather with word and action that all of us make mistakes and that perfection is not the qualification of him being a part of his family, my grandfather would have lived the rest of his life with half of his self on the far side of a valley between himself and himself. He would have been an amputee of the most amputated kind of body: a body missing the felt sense of it belonging and mattering to other bodies.

The love that my great grandfather gave to my grandfather in the decisive moment of his life is the same love that my grandfather could then give to my mother when he raised her. It is that love with which my mother has always loved me. By building a bridge where there had been a barn, my grandfather’s grandfather re-membered all of us, even those whose face he wore before we were born.

I share this story in this blog because there are millions of people around the world, and thousands within a short walk from wherever you sit or stand reading this, who feel that there is some thing about them that disqualifies them from being a part of the community. Because of some kind of “with” that they are said to have—like, for instance, because they are a person with dementia—they lack the feeling that they belong and matter to the human community in a full on, non-diluted sort of way. Having that feeling in one’s lived body is a kind of pain. It may well be the most painful kind of pain that a human being can ever know. It is not a pain that any kind of pill can make go away, however much a painkiller (prescribed or otherwise) may numb it. Nor is it a pain for which we will ever find a technological cure. Any “cure” that would cure that kind of pain would “cure” us of our humanity at the same time; and may we never be so technologically advanced or fortunate.

For this form of suffering, there is only one form of healing. It is often considered mawkish to use the word love. I understand the reaction. It is a word that probably means as many things as there are people who use it, a word that may well be used as falsely as sincerely, and may, if used lightly and too often, desensitize us to acts of total self-giving and other-receiving that defy categorization. And yet, the fact remains that there are expressions of suffering that only the experience of another person’s total acceptance of us, as we are, can heal. If no word does justice to that kind of inexplicable grace, maybe it is because such a grace seeks life in our body more than defining in our heads.

My dedication to learning to be with people with dementia began in my gratitude to people who extended themselves to me, no strings attached, when I least expected it. I understand what it means to be “wiped out,” in other words, for the same reason that I imagine most people do: I’ve been wiped out before: I’ve felt that terrible feeling of not being sure that I belonged here, of not being sure—sure in my bones—that my existence really mattered, even to me, especially to me.

Mistakenly, we have told ourselves as a society that people with Alzheimer’s disease slowly lose their mind. That’s what the word dementia means etymologically: “de” as in “away” and “men” as in “mind.” But that is to make sense of the experience from the perspective of an outside observer. From the inside perspective of a participant, dementia means what it feels like, and what it feels like is the losing of one’s body, by which I mean one’s social body—the body in which one feels that he or she belongs and matters. This is the dis-ease of Alzheimer’s, and it is a dis-ease that has been entirely overlooked in our national and global campaigns to cure Alzheimer’s disease.

It is a dis-ease, however—and here is the good news—that everyone can participate in healing, no matter one’s educational credentials, since the only education that matters when it comes to being with people who need our undivided loving attention is the one we have received from those who have offered to us the same. That is to say, we can all build a bridge to someone with dementia—build it from our heart to their heart, our attention to their infinite worth. And with that bridge, and on that bridge, we can invite people with dementia to feel again that they are, and always will be, perfectly qualified to be here with us. That is the way we people with some thing heal we people with some thing

No amount of cognitive impairment—none—impairs a person from feeling that love is listening to her.

May we be with each other the bridge of love’s listening.

Michael Verde

memorybridge.org